"A Myth and a Prayer" – Article and Conversation about Mythology with Gregory Gronbacher and Willi Paul from Planetshifter.com Media

"A Myth and a Prayer" – Article and Conversation about Mythology with Gregory Gronbacher and Willi Paul from Planetshifter.com Media

"Myths are public dreams. Dreams are private myths. By finding your own dream and following it through, it will lead you to the myth world in which you live. The passage is from dream, to vision, to the gods... and they are you. All the gods, all the hells, all the heavens are within you. The God is in YOU. It is not something that happened somewhere else a long time ago. It's in you. This is the truth of Truths. This is what the gods and myths are all about. So find them in yourself and take them into yourself and you will be awakened in your mythology and in your life."

- Joseph Campbell

"Our future depends on our willingness to abandon worn out methodologies and outdated ways of reading the Judeo-Christian myths. These grand narratives must be read again with fresh eyes, the advantages of science, and our better modern sensibilities. To continue to read them in literalist fashion is to harm the original intent of the ancient authors, the underlying truth of the texts, and to ruin any opportunity for our culture to once again embrace their underlying sanity."

- Gregory Gronbacher

* * * * * * *

Please enjoy author and seeker Gregory Gronbacher's excellent article:

Looking back to look forward – explorations in comparative mythology, reproduced in full after our conversation.

Willi: Have you had experiences that fit into Joseph Campbell's initiation, journey and hero scheme?

Gregory : Somewhat. I'm reasonable enough to avoid casting myself as a hero too often. Also, I find Campbell's overall trajectory somewhat excessively individualist and tainted by the myth of progress. Yet if this schema fits my experiences at all, it's in the spiritual-religious arena. I've undergone being called out of ordinary, everyday life into an adventure that took me far from my starting point, brought excitement, openness, and then ordeal, struggle, and sometimes victory.

My initial religious experience was a spiritual awakening, at age 15 in a Catholic setting (I was raised nominally Lutheran, but more or less secular, maybe even High Pagan.) This awakening was a call out of ordinary, everyday life, to an adventure in worlds I never knew existed. I ended up converting to Catholicism and earning advanced degrees in theology and philosophy and even at a point working for the church as a lay theologian. I benefited greatly from the journey and adventure with Catholicism, but my ordeal came in my early 30s with issues of maintaining integrity (intellectual, practical, and spiritual), refusing to bow to an abusive, controlling institution, and eventually renouncing the church and entering a period of spiritual wandering.

I traveled through Buddhism, Taoism, forms of Paganism, Atheism, and attempted a few return journeys to a more progressive, lesser institutional Christianity. These returns luckily failed, since such a path for me would have been regressive. Currently, I am immersed in Reform Judaism, but I struggle with primal, underlying eruptions of yet another call (which I seem to be refusing, or perhaps delaying) toward what I might describe as a Humanistic Druidry - an ecospirituality that has much overlap with your work on sustainability and which is focused more on caring for nature, others, and self, and less on deity, iron age myths, moral purity, and tribal commitments.

I appreciate the Jewish community and love the beauty of Jewish theology. And it's possible that the call I sense is a call to integration and not departure.

Yet I am being compelled by my own thinking and evolution toward what for me would likely be a more genuine spirituality to match my thinking on divinity, cosmology, ethics, anthropology and one that would better sync with my own experiences of the world. This is possible within Judaism, but it would take effort. Yet the alternative requires effort too – the effort of building a new tradition.

And I can't help but be convinced that I am not the only one being drawn to this path and journey, that some sort of global awakening is underway with the collapse of Abrahamic traditions and their exhausted cosmology - toward an emerging spirituality of right relationship with nature and with others. This spirituality would be one of meditation, mindful living, mutual cooperation, justice and sustainable living. Once it emerges more fully, I believe will prove revolutionary - and popular.

Willi: I am creating new Nature-born and modern community sharing rituals. Spiritual not religious in construct. Do you share this calling? Any examples?

Gregory: Well, that depends on how you define spiritual and religious. If by spiritual and not religious you mean non-restrictive, relying less on institutions, free-flowing, open, and allowing for personalization, then sure. But if you mean "anything goes", no intellectual foundations, fuzzy thinking, no boundaries, no principles – then I can share much of your efforts, but will likely find them without adequate foundations to endure or be meaningful in a communal setting. If spirituality becomes too idiosyncratic, it becomes difficult to ground community around such.

Willi: Can the community be the hero now?

Gregory: Yes, I think we may be witnessing a move away from the unhealthy individualism that has us all embarking on isolated quests toward an awareness that we are moving forward, evolving in a collective, communal way. The best journeys are a mix of personal and communal affairs. Additionally, the notion of the separation of the individual from the community is somewhat artificial.

Willi: Good. Folks from my third Mythic Roundtable think that the hero is now integrated into the Campbellian triad and that the "evil" monsters are actually us; that the monsters are part of the community now. A nice paradox?

Gregory: Yes, I do like that addition and insight. I don't want to eliminate the notion of the other completely. There can be people committed to such evil that they indeed do separate themselves from others and force that identity upon themselves and deserve marginalization. I think it's rare, and even in these cases, such individuals reflect those parts of us and the community at least in shadow form.

Willi: Can you offer a critique of Campbell's work in this Drought – ISIS – GMO Age?

Gregory: I tend to agree with John Michael Greer, Peter Grey, Richard Heinberg, and Jason Kirkey (and others) that we are in a period of decline and transition. What's declining is Western Industrial culture and infrastructure. What's keeping most people in denial about our decline is the pervasive myth of progress - that the human trajectory is always upward to something better.

This myth is preventing real solutions to our growing problems from gaining traction, too.

I'm not a Campbell scholar, but I think Campbell's basic schema of the Hero's Journey is tainted by the same attachment to progress and guaranteed happy endings. Campbell wasn't a blind idealist, but he still often seems convinced that progress is a certainty. There are not enough chthonian aspects to Campbell's sense of the spiritual journey.

Our age of ecological upheaval, ISIS, fundamentalism, GMO (et al) - what may emerge from our ordeal with these things (symptoms and by-products of the collapse) may not be what some expect. We are likely heading for a humbler, slower, simpler future that will please some, but horrify others who expect an endless supply of ever-better and cheaper iToys and living without concern for nature or others.

Willi: Please tell me who controls our mythic trajectory right now and how you and I can engineer (your) "humbler, slower, simpler future."

Gregory: I think we all control our mythic trajectory, but obviously those of us aware and engaged will likely be more influential. As I type that last line, I stop and wonder if I am overly optimistic? I think of the stunning amount of messages/images/symbols/narratives being tossed at us, forced on us, thrown at us, shoved at us – by government, by corporations, by their marketing and propaganda, and even by mainstream religion that too often tries to control the culture at large.

Humbler means less certain, more skeptical, less ideological, more realistic, more grounded in reality and not abstract, speculative theology. Slower means meditative, gentle, willing to allow to address others as persons of dignity, not forcing our ideas, not forcing decisions, engaging in conversation rather than preaching at. Simpler means stripped down to the bare essentials – I think of Judaism – it's rich, but not always simple. It could benefit from simplicity – from eliminating much of the tradition that is today outdated – redeeming the first born son, circumcision, religious purity laws, certain parts of Kashrut – much the same project as offered by Reformed Judaism to mold Judaism into an Ethical Monotheism accessible to all with a universal message of love and justice.

What I love about Reform and other forms of Liberal Judaism is the dynamic hermeneutic, the requirement that every Jew of every age join the conversation and make an interpretative contribution. Who controls the Jewish mythic trajectory? Every Jew has a say in that trajectory.

Can Judaism be the vehicle for a humbler, slower, simpler future? I'm not sure.

Willi: Why should we care about the classic myths? About mythology at all?

Gregory: Mythology helps shape culture, and therefore history as well. Myth helps us find our place in the world, establish an identity, and often convey practical wisdom on how to live. Some have argued that we live in an amythic age. That may true, but knowing the myths that have shaped our culture as well as other cultures is an exercise in self-exploration, learning from the past, and seeing more clearly toward the future.

Willi: Who really cares about the past and why?

Gregory: Sadly not enough people care. But if you don't know where you come from how can you know where you going, no less who you are? Context offers perspective and nothing grants context like the past. We need not be chained to the past. We not be overly enamored with it, but we need to understand it as best we can. It's not just that we risk repeating the mistakes of the past, it's that we honestly can't fully understand who we are without the past.

Willi: Please share a few examples of what you call: "grand existential narratives?" Who gets in? Who gets left out?

Gregory: I really like the way you phrase this question, that is, the latter part concerning who is in and who is out, who is included and who is excluded. Most myths are tribal. They relate to a specific people. As such, they often easily shift into exclusionary mode - "our" gods, "our mission", "our message", "and our heroes" and so on. Also, many myths tend to create or proclaim foils - who is the bad guy, the enemy, the "other". This can create not merely tension, but lead to hatred and violence.

Narratives become grand and existential when they take on universal themes of human existence and offer themselves as stories that everyone can engage and relate to. Many Native American creation myths are an example. As is the creation stories in Genesis. I'd add that some Celtic myth also approaches this status with an emphasis on nature and honorable living - even if it's clothed in warrior images.

Concerning who is in and who is out? I think in our current myth of progress anyone who doesn't successfully manipulate the system and play along with the corporations is out. And by out I mean marginalized, even sometimes crushed. I think the myth of progress - which is our current grand narrative - has racial exclusions, gender exclusions, and despite its homage to individuality and self-expression, is really quite conformist. Not all diversity in nature is a good thing - think of cancer. But in general, diversity in biosystems is healthy and contributes to endurance and thriving. Permaculture appreciates diversity in a healthy way and a way from which we must learn.

Willi: How would you facilitate a neighborhood myth making seminar in East Oakland? Please include relevant symbols and Universal theme(s)?

Gregory: I've never been to East Oakland, so I hesitate to offer anything too concrete. I grew up in New York City, went to college in Ohio, spent 5.5 years in Europe, and now have lived for the past 20 years in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

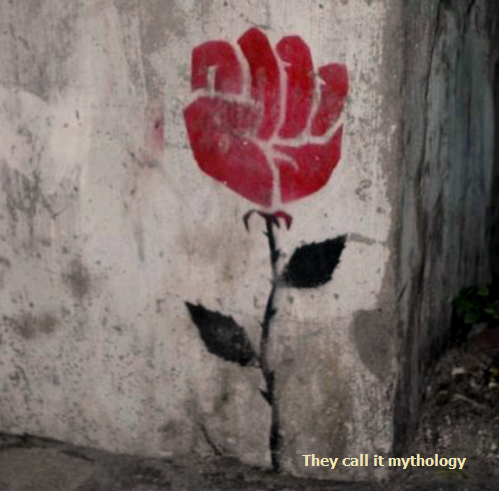

I think relevant symbols would include those from traditional religious systems – crosses, stars, pentagrams, crescents – but should also include newer and evocative symbols – spirals, circles, drums, dancers, astrological signs, etc. Further, I would give prominence to the newer symbols. Also, those who knew the local culture could add what might be locally recognized, meaningful, powerful, and even controversial.

Willi: Symbols and archetypes - What are they in your work and how are these things changing, if at all?

Gregory: Well, the Cross remains for me a powerful symbol of the healing restorative energy of kenotic love. Yet I think this truth about kenotic love remains even when one filters out Jesus and Christianity. There is nothing necessary about Jesus. (Or Torah for that matter.) I see the power of the symbol of the Cross, but I've divorced it from the more incredulous aspects of the narrative and system from which it emerges. Somehow, the message of the Cross needs to be interwoven into our newer spiritualties and systems of thinking - it may not take the shape of a cross, but the insight of kenotic love needs to carry forth.

Celtic knot work remains evocative for me - serving as a symbol of reality's interconnectedness and interdependence.

The spiral is also powerful - calling to mind evolution, both cosmic and personal.

The Well of Segais also serves a transformative image for personal meditation - as a place of rooting, of restoration, and of origins.

The Star of David is another symbol. No one is quite sure where it exactly originated. It's likely pagan in origin. Common interpretations include two intersecting triangles – one representing the divine impulse and the other nature.

Willi: Please see this symbol/ archetype tool kit disguised an article and reflect for us:

Gregory: Oddly, looking at the photos reminded me of Israel for some reason. I've never visited, but the images of Israel are of agricultural renewal, development, community, and nature. The image that spoke most movingly to me was the tree and the moon. The moon is a symbol of the Jewish calendar. The full moon marks many Jewish holidays. The tree is representative of Torah which is often called a tree of life. Further, the symbol spoke to me of autumn, of Samhain, of endings and beginnings.

The explanations of the symbols and the writings were evocative of much the same. Also, they spoke to me of my own project of blending and revitalization.

Willi: Are you religious or spiritual? Both or none?

Gregory: Both. On one level, I accept that many use the terms interchangeably in casual conversation. Yet I also see important distinctions between them. I tend to approach religion from the perspective of its etymology - from the Latin word to bind. Religion is a set of practices and traditions that bind together a worldview. Spirituality, from my way of thinking, is more open and free flowing and focused on the process of determining and exploring that worldview, asking existential questions, and examining our own experiences of living.

Right now, as a Jew, I have a religious system to anchor my spirituality. If I heed the call that I believe I am experiencing toward ecospirituality, then I will have to join in the creation of the religious aspects of forming a tradition. And this won't be easy, because many drawn to nature based spirituality are Romantic types who shun system, doctrine, and the institutional aspects of religion that both restrain and maintain spiritual impulses.

Judaism is a religious system that has survived for thousands of years. If I embark on an ecospiritual path, I will certainly take much of the form of Judaism with me, applying it as a way of grounding newer expressions of spiritual seeking.

Willi: Can you compare pagan mythology with Jewish mythology and tell me if you can see a unity of spirit coming?

Gregory: I hope so. Earlier I commented on my own feeling called beyond Judaism to a more nature-based spirituality. A large part of me thinks and feels that perhaps the call is not to leave Judaism, but rather to stay and integrate nature-based insights into Judaism – not superficially, but in a more full sense. Such a project would likely not be popular with some, if not many.

Pagan mythology is broad – from many cultures, many centuries, and many peoples – and is both old and new. Jewish myth is more concentrated, edited, redacted, and collected into resources most Jews are aware of. I appreciate both collections of myth.

Yet I believe that Jewish myth stresses both the dignity of humans as well as the dignity of nature, caring for humans as well as caring for the ecosystem. It frustrates me when I read pagan theology, pagan writings, and pagan myths and find more concern for trees and rivers than human beings, more concern about backyard farming or solar power than feeding the poor and reintegrating the homeless.

Some may find my sentiments to be overly simply. But I'd be happy to be challenged or even refuted.

Judaism has much overlap with Paganism – at least in terms of structure. First, the nature-based aspects are many – the Sabbath starts at sundown, the calendar is lunar, the new moon is a feast day, there are many nature-based epiphanies throughout Torah – burning bushes, pillars of fire, thunder, cloud, rain, and whispering winds. Nearly every Jewish holiday has an agricultural significance which allows the Jewish holidays to form an alternative Wheel of the Year.

Jewish notions of Divinity are not what many people think – there is much room for approaching God as an archetype, for understanding God in a panentheist fashion, finding the Divine infused throughout nature and being most powerfully revealed in the cycles of agriculture, the unfolding of the seasons, and in the rhythms of the moon and tides.

So, perhaps my sense of being called further is a call to integration and not departure. Time will tell.

Willi: "- Jewish myth also had something many of the other myths lacked – a strong, revolutionary alternative track of mercy, love, generosity, care of the poor, and justice." Are you speaking about history or today?

Gregory: Both, but sadly, more so history. There is a moral genius in ancient Jewish myth that in my opinion is lacking in other mythic systems. The concern for justice, love of neighbor, care of the poor - these themes are not substantial in many other ancient myths. Sadly, many Jews today don't engage their myths and thus this moral revolution is often a thing of the past.

Recent news about Jewish-Israeli settlers destroying the olive trees of Palestinian farmers is horrific, sad, and tragic. It shows how many Jews today, even self-proclaimed religious ones are out of sync with their own myths. Torah clearly states that you should not destroy the trees during war and that you should leave the loser with the agricultural means to survive. Destroying olive trees - symbols of peace and continuity - is gross immorality.

I think the moral concerns present in Jewish myth will need to carry over in new myths that we tell and live. I am highly drawn to many of today's Neopagan-Druid myths concerning a love of nature, care of the ecosystem, reenchanting nature and once again capturing a sense of its sacredness. But what is often lacking is the emphasis on human dignity and inter-human morality - the same holding sacred of humans as nature. Any lasting and valuable spirituality has to honor both nature and persons.

Willi: I found your use of the word (re)enchanting strangely powerful. Where can we find enchantment today?!

Gregory: I believe we can find reenchantment in wilderness, in nature (I offer the distinction between an urban park and a nature preserve in Alaska or somewhere remote, as an example). I believe we can find reenchantment in some forms of religion with whatever we deem and actually treat as sacred.

Enchantment is when we find something sacred, alive, special, transformative, engaging – when something reminds us of deeper questions and existential issues. Enchantment happens when something inspires awe and connects us to the essential wholeness of being.

I think some find enchantment in church (although I think less people are doing so, thus the drop in members and participants), some in astrology, some in story, some in cooking, some in magic, some in the occult, some in hobbies – the possible arena's for enchantment are many.

Willi: I have spent many years transforming Permaculture and Transition movements with a Quaker POV into new myths. I would like your critique.

Gregory: I've only started reading and wrestling with your work, thank you for sharing it. It's fascinating and offers so much - overlapping with many other projects of nature based spirituality moving in the same direction. I will indeed be spending more time with your writing and interviews. Some initial impressions:

First, I deeply appreciate your definition of myth and its relationship to truth. Philosophers can often forget the subjective-personal aspect of truth that doesn't erase its objectivity. A story can be true, but not appeal to all. Thank you. Second, the notion of permaculture is one that must be part of any nature-based spirituality - and these seem to be the slowly developing spiritualties that I am convinced will become dominant. Yet many of these spiritualties are what might be called "soft" they haven't moved yet to the more serious work of eco-activism and responding to the needs of nature and humans. Permaculture offers a strong and practical foundation to channel this impulse.

If I had to offer a critique, it would likely be more in the form of a reminder to all of us attempting to develop myth, ritual, and new spiritual systems - is tough work. It takes more time than we think. It's even painful at times. I really don't think we've grasped the significance of what we are doing.

Willi: A comment. Many permaculturists actively protest any connection to religion in their science-based design. Part of my mission is to share the significance, or holism, in all things Nature.

Gregory: I can totally understand that. But human meaning is intrinsically entwined with nature. And that meaning is also part and parcel of spirituality in its most basic aspects. I'm not advocating we worship permaculture, or even nature for that matter. But I am an advocate of allowing nature to serve as a spiritual touchstone. Therefore, I share your holism and your mission.

Willi: Are there brand new creation myths emerging? Similarity, do you see new apocalyptic myths rising?

Gregory: Yes, I think new creation myths are emerging which focus on evolution, singularity, and the Big Bang - the scientific foundations of our current understanding of cosmogenesis.

Yet for these myths to become narratives, they will need poetry, plot, and artistic treatment so as to be accessible to people in general and appeal to more than the intellectual.

The advantages of this mythic approach is that it harmonizes with other insights of interconnectedness, unity, mutual responsibility, and human enmeshment in the web of life, as opposed to somehow standing outside of it, apart from nature.

Willi: Can sounds be catalysts to a higher consciousness? Please share your thoughts on sound symbols, archetypes, and new myths. The connection is here:

Gregory: Yes! I have experienced sound as such a catalyst. For me, there is nothing quite as meaningful and moving as hearing the return of the song birds – it's a sound of hope, or renewal, and a source of epiphany. Many other sounds of nature have the same effect on me, and others.

Music has an inherent spiritual quality. The power of music is evident across the various styles of music. Why else do we incorporate music into liturgy?

Drumming, chanting, meditation bowls, bells – are all instruments of awakening, transformation, and connecting.

Willi: What are the source(s)?

Gregory: Brian Swimme, Thomas Berry, Loyal Rue, Ursula Goodenough, Jason Kirkey, and others. In Jewish theology, the work of Arthur Green, Jay Michaelson, and the folks who form Wilderness Torah are about a similar project.

* * * * * * *

Looking back to look forward – explorations in comparative mythology by Gregory Gronbacher

Our current Western industrial way of life is in a period of transformation marked by cultural and practical decline. Many are in denial about our current state, but the evidence of our current decline is building. Our myths, religions, and economies are exhausted – chaos is seeping out along the social margins.

Decline is not the same as extinction. The West will survive, but only by embracing new myths, forms and structures, and likely after a period of disruption. What is certain is that Western ways of being religious – the traditional source of our myths – are changing rapidly and in ways that will likely surprise us.

Openness to reality and the effort to avoid narrow ideology is the foundation of wisdom and restoration – we must allow ourselves to be informed by our experiences and reflection on them – not be limited "isms" that attempt to force reality to comply with their theories – we must live according to the truth if we are to once again have a thriving economy, functioning political order, moral culture, and religious and spiritual sanity.

Truth matters and humans encapsulate our core truths and find our meaning and place in the world through stories. The human person is a story-telling, metaphor-loving, symbol-making being for whom myth conveys information regarding fundamental, existential meaning. The human person relates on a psychological-spiritual level to stories, narratives, icons, and parables.

Myth – grand existential narratives – provide a culture with its central narrative(s), thus establishing the framework for wisdom – a collective sense of purpose, place, identity, and set of shared values. Therefore, the language of spirituality is that of myth, metaphor, and symbol.

We live in the age when the Judeo-Christian mythos that sustained Western culture is decaying, most likely beyond the ability to revive and invigorate the culture in their current reading. Only an interpretative revolution and vibrant rereading will reinvigorate them. As our once central myths erode, the West currently suffers from an increasing anarchy of meaning and value, and is tending toward nihilism.

Shatter the shared mythic narratives and symbols that provide a culture with its basis for collective thought and action, and you're left with a society in fragments, where biological drives and idiosyncratic personal agendas are the only motives left, and communication between divergent subcultures becomes impossible because there aren't enough common meanings left to make that an option.

Many scholars and mystics believe that only religion can accomplish the fundamental unifying task. Nihilism becomes self-canceling, once reflection goes far enough to show that a belief in nihilism is just as arbitrary and improvable as any other belief; that being the case, the assertions of a religious tradition are no more absurd than anything else, yet when based on humane values often provide a more reliable and proven basis for commitment and action than any other option.

The only way to avert the slide into nihilism's abyss is to revitalize our sacred narratives and myths. And key to the revitalization is the updating of the Judeo-Christian mythos with a variety of insights, including those from evolution, science, organic systems-thinking, psychology, and social science.

A Multiplicity of Myths

Western culture has many mythic systems to choose from. The culture of the Roman Empire coalesced around Virgil's works that depicted in mythic form the Divine purpose of the Empire in total military conquest of the known world. The Aeneid, which appeared around 19 BCE provided the story in which nearly all Romans found themselves and saw themselves.

Beyond the boundaries of the Roman Empire, the so-called "barbarians" lived in cultures animated by their own mythic systems.

The peoples of the Scandinavian countries had their traditions of oral stories passed down through the centuries. Eventually, these stories were written down in the now famous Eddas – poetic stories of the Vikings and their conquests, conflicts, and way of life. These stories of valor, magic, and warrior culture were finalized in written form in the early 1200s CE.

The Celtic peoples also lived in a mythically rich culture – with variants of national myths abounding among the Irish, Welsh, and Scottish. The Ulster Cycle, the Myths of the Four Invasions, tales of Queen Maeve, Cul Cullen, and other foundational stories each taking on their own flavor depending on the tribe telling it. Again, these stories existed once only in oral form, to be committed to writing centuries later. The majority of the Celtic myths being written down between 900-1100 CE.

All these myths reflect the aspirations, values, goals, and self-identity of the peoples from which they emerge and in turn help shape the same in future generations.

Common to the vast majority of these Western myths is violence, trickery, the sexual power of beautiful women, the nobility of the courageous warrior, slavery, and glory through military conquest. There are indeed traces of kindness, forgiveness, mercy, and generosity – but these values are secondary in importance compared to honor, courage, and bravery – usually exhibited in warfare and armed conflict. As for women's rights, basic human rights, and the care of the poor – not much ink is shed.

The Myths of another Tribe

As the Celtic peoples were telling their stories by the village fires of ancient Europe, another tribe of people had already committed their foundational narratives to writing. These people – the ancestors of what today we call the Hebrews, Israelites, or Jews – lived in the area of the world once called Canaan, today called Palestine and Israel.

Jewish myth had its fair share of violence and war. On a few occasions the ancient authors write of Divine calls to genocide, the need to stone adulterers, unruly children, and those who worship improperly. Jewish myth has its tales of glory in war and violence at home. It reflects the mores of the time.

But Jewish myth also had something many of the other myths lacked – a strong, revolutionary alternative track of mercy, love, generosity, care of the poor, and justice.

The same set of myths that calls for slaughtering the women and children of conquered towns, also has an undercurrent of loving your neighbor as yourself, welcoming the stranger, radical hospitality, tolerance, and the glorification of peace as well as war.

Jewish myth features commandments that set it apart from other mythic systems – gleaning, a trend away from capital punishment, environmental concern, and humane treatment of animals, a strong call to care for the needy, poor, and marginalized, and a foundational yearning for radical justice.

Jewish myth lays out hints of an economic system based in agricultural fairness, the sharing of land, and the periodic forgiveness of debt.

Jewish myth calls for limitations in warfare and conflict – don't burn the trees or sow the land with salt. Leave something for the losers to survive upon.

Jewish myth – much of which predates other Western myths by centuries, contains something missing from most of the other mythic systems – mercy and a drive toward humane culture.

To be clear, I am not blind to the violence and nastiness that is all throughout the Hebrew Scriptures. Yahweh has to be talked in off the ledge more than once. His hand of wrath has to be stayed by more sober and merciful voices of reason.

Yet the seeds of justice, love, peace, and tolerance are there in ways they are not in other mythic systems. And the interpretive freedom, the inventive hermeneutic, and the traditions of Midrash and relevancy reading do not exist in other cultures as strongly or in some cases, at all.

Our best scholarship and the best of archeology, cultural studies, and history shows that the Jews originated from among the Canaanite peoples, assimilating the local culture into more peaceful and just ways, rather than taking the land by conquest after a physical Exodus from Egypt. The myths of these peoples reflected innovative and revolutionary values as well as the common values of ancient peoples.

Adopting the Jewish Interpretative to Myth

Revelation is a continuous process, confined to no one group and to no one age. Yet the Tanak (Jewish Bible) combines history remembered with history metaphorized, expressing sacred myths that are primarily sweeping spiritual statements, providing context for answers (but not necessarily the answers themselves) to life's basic questions. Jewish identity and personal spirituality requires weaving our own experience into these myths to form a narrative context for our life.

Scripture recognizes the Sacred Presence that communes with humans throughout history, hidden in all that happens in the world, and testifies that this Power is concerned with holiness and justice. The writings are our ancestors attempt to give voice to that Presence the best they could, through storytelling, poetry, analogy, and rule making. That voice was imperfect, but progressive.

The texts contain our ancestor's thoughts about God's will and wisdom, but not God's dictated words. The sacred texts are not inerrant or infallible – they are a collection of inspired writings that recorded our ancestor's understandings of the Divine. The texts cannot serve as historical or scientific documents, and their moral application must be subtly, culturally applied. Since Torah consists of many viewpoints, and sometimes contradictory ones, our reading is always selective.

Scripture contains revolutionary ideas and timeless truths – the equality of all humanity, the equality of men and women, and the inherent dignity of all human life created in the image of God. It dictates love of strangers and calls for the care of the poor and the downtrodden. It bespeaks the dignity of labor and the need to treat workers well and pay them proper wages. Its vision remains vital for Western renewal.

Literal readings render the core myths irrelevant. We are right to reject the ancient views of sacrifice, patriarchalism, family structures, and violence that are incompatible with a contemporary understanding of the world. Despite this necessary filtering, the Biblical writings contain a core of insights that still ring true and animate contemporary Western culture and spiritual practice.

We are to apply the texts to our current realities – with both the text and our current understanding of reality in dialog, neither trumping the other. The texts are living and meant to speak to every generation.

To do so, each generation must engage the texts in an ongoing conversation. Every Jew (and Christian who claims the texts as their heritage, too) has a voice in this conversation and a role in the Bible's ongoing reinterpretation.

We can no longer be religious in the same way as our ancestors. The world has been irrevocably transformed and so have our patterns of thought. We must find ways of engaging iron-aged myths with postmodern thinking. What is required is critical naïveté – the ability to recognize myth for what it is, move beyond the literal concerns, and then, with updated knowledge, engage the myth allowing it to inform, engage, and transform us.

Toward Mythic Renewal

Ancient Israel was a people who preferred peace, believed they were obligated to the poor, and set themselves on an arc of justice that continues today in the better aspects of Western culture.

Christianity built on this mythic tradition of mercy, furthering the more humane aspects of the West.

Our future depends on our willingness to abandon worn out methodologies and outdated ways of reading the Judeo-Christian myths. These grand narratives must be read again with fresh eyes, the advantages of science, and our better modern sensibilities.

To continue to read them in literalist fashion is to harm the original intent of the ancient authors, the underlying truth of the texts, and to ruin any opportunity for our culture to once again embrace their underlying sanity.

* * * * * * *

Gregory's Bio –

Originally from New York City, I've called the West Michigan area home for the past 20 years – it too, is a space in between – a pleasant place nestled in between coasts, cultural craziness, and crowded cities.

I'm a married homebody with high social needs who loves to read and engage in good conversation with small groups of friends. Before I got in touch with my more grounded, introverted inner self, I got around, mostly for educational purposes.

I attended Franciscan University in Steubenville, Ohio – a vibrantly Catholic, solidly liberal arts school, where I majored in politics, theology, and philosophy. Next came a year and half in Liechtenstein for my M.Phil. in philosophy and political theory at the International Academy of Philosophy. I followed my time in the Alps with three and half years in Ireland, doing my doctorate in philosophy (and being blessed) with the Jesuits in Dublin.

Christian social ethics, free market economics, natural law approaches to ethical reasoning, personalism, social philosophy, classical liberalism, phenomenological realism, and the various theological touch points of these areas have formed me, my thinking, and my theology, and have always captivated me.

My theology is progressively rooted in tradition. My approach is mythical-allegorical. I tend toward the existential and even the Jungian. I believe the encounter-dialog-reading of our scriptures is ongoing and evolving. I find the Divine presence in nature, much like Moses did at the burning bush, and I find the revelation to be similar – God is the ground of being, the patterns of order in nature and the world, the source of life and goodness.

I believe religion's purpose and meaning is to make us better people – individuals who are capable of love and generosity. I believe we can be transformed by engaging our myths, symbols, and liturgies. I believe prayer is the sanctification of the expressions of the heart and a form of meditation. I believe the heart of religion is found in the teachings of "love your neighbor as yourself, love the stranger in your midst; walk with humility, practice kindness, show mercy, and strive for justice."

My spirituality has evolved to where I occupy "a space in between", rooted in Liberal Jewish theology and belonging to a Reformed Jewish community, but with my theology colored by insights from Progressive Christianity and nature-based spirituality and mediated through my own Celtic cultural heritage.

I invite you to join the conversation and I welcome dialog, questions, and all comments.

Willi's Bio –

In 1996 Mr. Paul was instrumental in the design of the emerging online community space in his Master's Thesis: "The Electronic Charrette." He was active in many small town design visits with the Minnesota Design Team. Willi earned his permaculture design certification in August 2011 at the Urban Permaculture Institute, SF. Mr. Paul has released 20 eBooks, 2260 + posts on PlanetShifter.com Magazine, and over 325 interviews with global leaders. He has created 68 New Myths to date and has been interviewed over 30 times in blogs and journals. Please see his cutting-edge article at the Joseph Campbell Foundation and his pioneering videos on YouTube. A current focus is Myth Lab – a technique that Willi is implementing in his current Mythic Roundtable series.

* * * * * * *

Contact Info -

Gregory Gronbacher - homeswithgregory at gmail.com

Willi Paul - willipaul1 at gmail.com